Climbing Ropes - A Concise History of Materials & Construction

The climbing rope is perhaps the most recognizable and important pieces of equipment used by rock climbers and mountaineers. Serving as a means to physically connect a team of climbers together, the rope is also a symbol of the emotional connection between climbers - the bonds of camaraderie and trust forged in the world’s high and steep places.

A staggering array of ropes and cord are available to the modern climber by many different domestic and foreign manufacturers. The safety record of nylon climbing ropes is excellent; in fact, no modern rope of 9 mm diameter or greater has ever been reported to fail due to a simple lead climbing fall. Given the proliferation and safety record of modern climbing ropes, it is easy to overlook the enormous improvements that have been made since rope was first used as a climbing risk management strategy (which began during an era where many top climbers did not live to see past the age of 30) [1].

Climbing ropes used during the Golden and Silver ages of climbing (starting with Alfred Wills’ 1854 ascent of the Wetterhorn and ending with W.W. Graham’s ascent of the Giant’s Tooth in 1882) were unsophisticated constructions of plant or animal fibers (e.g. hemp). Often handmade, the construction of these ropes were of laid or twisted rope, and were manufactured in a three-step process:

Construction of hawser-laid rope. Seamen’s Pocket Book, 1943

Laid Rope Construction

In the first step of laid rope construction, fibers are gathered and spun into yarns. The direction the fibers are twisted is called the lay; the letters S and Z refer to a left- and right-hand lay, respectively.

Next, yarns are then twisted into strands, and strands further twisted into a rope. The twist of the yarn is opposite that of the strand, and the twist of the strand is further opposite that of the rope. Traditionally, ropes made in this way using three strands are called hawser-laid ropes (Figure 1) [2].

Laid or twisted ropes have numerous disadvantages: they are not strong for their weight (a 9 mm manila hawser rope has a breaking strength of only 1,200 pounds!) [3], they are not very durable, and they are quite stiff. The hawser construction tended to result in a rope that twisted during use, which made these ropes frustrating to handle [1].

Most importantly, hawser-laid ropes had little to no stretch [1]. The resulting shock load during a fall could easily injure the unfortunate leader, or result in anchor/rope failure. Small wonder the leading climbing maxim of the laid rope era was “the leader must not fall!”

Nylon Climbing Ropes and Kernmantle Construction

In 1935, the DuPont Chemical Company invented nylon, which resulted in massive improvements to climbing rope technology. Nylon (polyamide) is a strong, elastic material, and this stretchiness improves the safety of a lead fall by dissipating the force of a falling climber over time. Nylon ropes were introduced by as early as 1940, with the German company, Edelrid, revolutionizing rope design in 1953 with the kernmantle design, which remains dominant today.

Kernmantle rope construction exposed by cutting open a rock climbing rope. Photo: David J. Fred

Nylon ropes solved the strength and elasticity problems of laid ropes; the remaining problems related to durability and handling (twisting). The kernmantle design solved these problems using a unique “core and shell” design [1].

The Kern – The Core of a Modern Climbing Rope

Construction begins with nylon filaments being spun into yarn. The yarns are twisted to form a ply, several of which are twisted together to form a bundle. Several of these bundles form the core, or kern of the rope.

The Mantle – The Shell of a Modern Climbing Rope

A nylon sheath (mantle) is then braided around the core (Figure 2). A number of variables influence the final properties of the rope, including:

the number of yarns

amount of twist at each step

tightness of sheath weave, and

the sheath braid

As an example, the cores of dynamic ropes are heavily twisted to produce stretchy ropes that can absorb the impact of a leader fall, while the cores of static (rigging) ropes are untwisted to yield a rope with little stretch. Typical kernmantle climbing and rigging rope diameters range from 8 - 12 mm [1].

Climbing Rope Testing Standards

Modern climbing ropes are manufactured and tested to multiple standards, including those of the European Norm (EN) and the International Climbing & Mountaineering Federation (UIAA). As a results, all rated, commercial climbing ropes produced by reputable manufacturers are quite strong.

Single climbing ropes must be capable of withstanding a minimum of five drops in a standardized UIAA drop test, which simulates a “worst-case” climbing fall using an 80-kilogram weight. The impact force the rope transmits to the simulated “climber” may not exceed 12 kN, a number determined via extensive testing on paratroopers by the United States Army [1]. Catastrophic internal injury to a climber will occur well before a tensile failure of a modern rope!

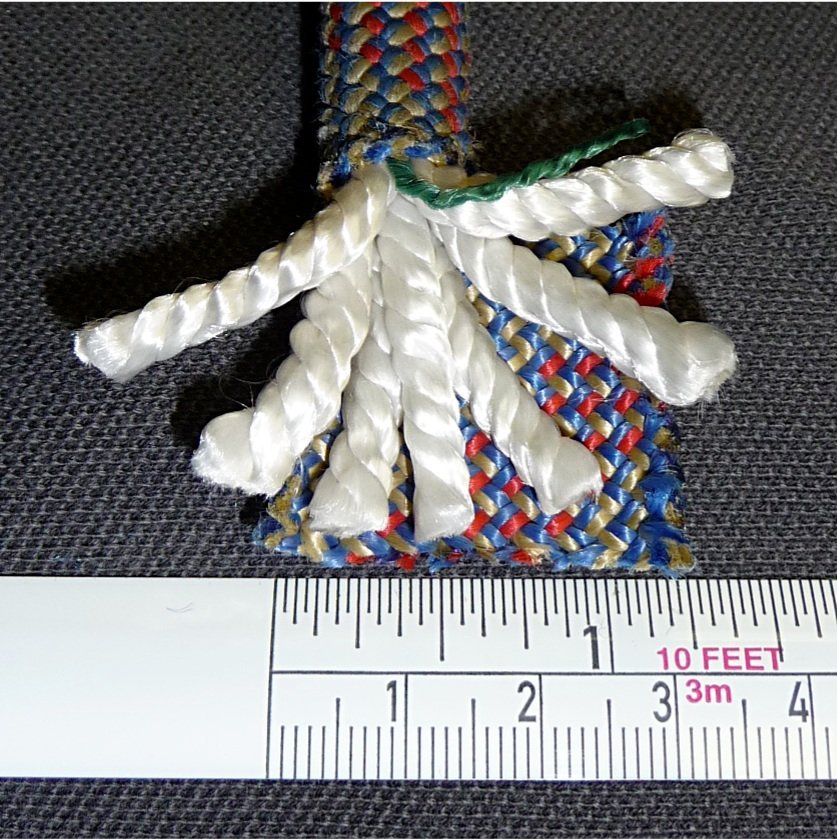

How Climbing Ropes Break / Fail

Most modern rope failures are caused either by rope abrasion over a sharp edge (ex. this case study where a rope snagged on the cornder of an auto-locking carabiner gate), or from careless rope storage.

Inspect Climbing Rope to Prevent Abrasive Failure

Make sure to inspect your rope before use; retire it if you find sheath damage that extends to the core, of if you find a section of damaged core. Damaged core is often indicated by a “flat” spot in the rope that has little resistance to bending. Ropes and other soft goods are typically retired after five years of active use.

Careful Storage & Use Prevents Chemical Rope Failure

Extended exposure to UV radiation or hazardous chemicals can degrade and weaken the nylon fibers that compose the rope. Store ropes in a cool, dry and dark place like a closet or rope bag. Avoid setting ropes on pavement or asphalt, where leaking fluids from vehicles will accumulate. Wash your rope regularly using warm water and a mild soap; do not use strong cleaners or detergents.

Summary

The rope is an essential climbing tool and an instantly-recognizable symbol of climbing fraternity. A great amount of research and development has improved climbing rope technology from its humble beginnings in the golden age of alpinism to its advanced state today. With proper care, your climbing rope will give you many years of great experiences on the rock.

Written and researched by Brian Fraleigh, with editing from Nick Wilkes.

Sources

[1] Bright, C. M. (2014). (thesis). A History of Rock Climbing Gear Technology and Standards. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.uark.edu/meeguht/41

[2] De Decker, K. (2010, June 28). Lost knowledge: ropes and knots. Low-Tech Magazine. https://www.lowtechmagazine.com/2010/06/lost-knowledge-ropes-and-knots.html.

[3] Manila Rope Strength. Engineering ToolBox. (2009). https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/manila-rope-strength-d_1512.html.

[4] Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (2014, October 30). Rope. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/technology/rope.