Auto-Locking Carabiner Gates Can Cut Climbing Rope Sheath

During a guided group top-roping trip in October, the masterpoint carabiners on one of our anchors cut completely through the rope’s sheath, exposing the interior core. This was the first time any of our guides had experienced, or even heard of, such an incident, so we wanted to share the details. The take-home message: Avoid using auto-locking carabiners as masterpoint carabiners on unattended top-rope anchors. Auto-locking carabiners often have sharp interior gate edges which, under certain circumstances, can twist so they cut into and damage or destroy a dynamic rock climbing rope.

Climbing-Rope-Core_Shot

EQUIPMENT DAMAGE

Psuedo Hawks’ Nest, East Rampart, Devils Lake State Park

Climbing rope snags on carabiner gate.

Another guide and I were managing a group of seven climbers at Psuedo Hawks Nest. We had three top-rope anchors set and I was belaying a client, Mike. He had just finished a climb and was about to be lowered 75’ back to the ground when he unexpectedly yelled, “The rope is coming apart!” I stopped lowering him and assessed the situation.

I was belaying while the other guide, Dawson, was on top of the cliff setting up a new route/anchor. Mike had climbed 5 routes that day, so he understood how lowering worked. Another client, Katherine, had already climbed the route and had been lowered without incident. She weighed approximately 100 lbs and Mike was approximately 200 lbs. When I started to lower Mike, I felt extra friction in the rope which was unusual, but beyond the extra friction nothing seemed to be out of the ordinary.

I asked Mike what he could see. He stated, “I can see the white of the rope and the orange sheath is pulled back.” He had been lowered approximately 10 feet over ledgy terrain and was still weighting the rope. I asked him if he could climb safely to a place he could stand, un-weight the rope and be comfortable until I could reach him. He stated he could, and I belayed him up approximately 5ft or less to a ledge he could stand on comfortably. I verified verbally that he was secure and told him not to move since I could not see exactly what he had done from my position. He stated, “Believe me, I won’t move.”

I yelled to Dawson, but it was windy and he could not see nor hear our group at the time. Since I could not contact him, I decided to hike to the top as quickly and safely as possible. I transferred the belay to another client using a weighted belay take-over, which allowed me to escape the belay while keeping Mike safe. I immediately left to reach Mike at the anchor.

When I arrived I found Mike understandably nervous, but doing well given the situation. He was in a relatively safe position, standing on a 1-foot ledge with good handholds, approximately 7 feet below the top. I handed him a 24” nylon runner with a locking carabiner and had him attach it to his harness and then clip the carabiner into the masterpoint. Mike was now connected to two systems: the compromised top-rope and my independent anchor at the cliff top.

At this point I made contact with Dawson, who gave me another rope to make the rescue more efficient. Using the second rope, my original anchor (which I verified was secure), and my belay device, I created a top-belay system. I then tied a figure 8 on a bight to the end of the second rope, attached a locking carabiner and handed it down to Mike. He clipped the locking carabiner to his belay loop. I then put Mike on belay and asked him to untie the damaged rope and drop it. He then climbed to safety at the top of the cliff.

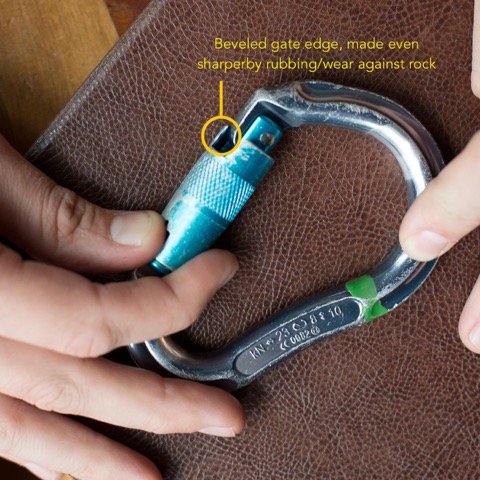

With Mike safe, we assessed what went wrong. We checked the masterpoint carabiners and found one of the auto-locking carabiners had a very sharp edge. It seemed this edge caught on the rope’s sheath and, when the rope was weighted, pulled the sheath back exposing the interior of the rope. We replaced both masterpoint carabiners with screwgate carabiners and dropped a new rope on the route. We re-checked all of the components of our system to confirm nothing had been displaced during the rescue. Once we had confirmed everything was in order, we felt comfortable continuing to climb the same route with the new hardware.

ANALYSIS

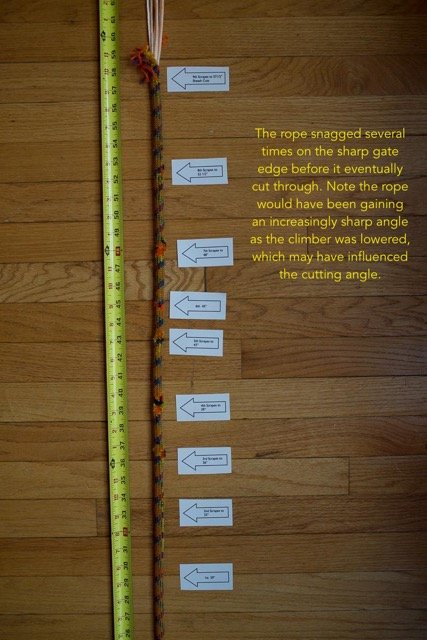

No one was physically injured, but the situation could have been worse. The rope sheath had been stripped from 2 feet of the rope, leaving the kern (the interior part of a climbing rope) exposed. Interestingly, the kern had not been visibly damaged. The series of photos above show what likely occurred.

We have researched the internet climbing community for similar situations, and also called climbing gear manufacturers to ask them their opinions. Evidently, this scenario is uncommon and we could not find any reference or documentation of this type of event occurring elsewhere. We also found that although auto-locking carabiners are marketed for rappelling and belaying they are commonly used by the climbing community in situations where the climber doesn’t want to worry about a carabiner coming unlocked, often in a masterpoint situation.

All auto-locking HMS biners we have looked at feature sharp upper openings on the upper gate.

We looked at several different companies' auto-locking carabiners (Black Diamond, Petzl and Omega Pacific) to see if this style of twist-lock sheath is an industry standard. We found all auto-locking carabiners with a twist-lock have similarly sharp edges on the inner portion of the locking barrel. That said, Petzl has modified their twist-lock carabiners from past year’s models to taper the edges and reduce the possibility of the rope coming into contact with the sharp corners. This change makes us wonder if this issue is wider spread than existing reports/literature indicate.

So, what to do with this new information? Clearly, sharp auto-locking edges can come into contact with soft goods (rope, webbing, etc.) if twisted the "wrong" way. Knowing that we cannot trust these carabiners any more than screw lock carabiners (which cost less, weigh less, and are more versatile), we have stopped using auto-locking carabiners in situations where we cannot verify correct orientation. This in effect limits auto-locking biners to use with belay devices and maybe safety tethers.

For further incident reports and analysis, please see Accidents in North American Mountaineering, an invaluable annual resource published by the American Alpine Club. ANAM has been an excellent educational resource for climbers for over 60 years and is a great place to read up on and learn from others’ mistakes.

I have not used the client’s real names and the article is not intended as a technical instruction for rescues. Please seek out professional instruction to learn basic rescue techniques. Author: Matt Hainstock